Table of Contents

Introduction

For much of the past decade, the Bluegrass Institute for Public Policy Solutions has led from the forefront of pension reform in the commonwealth of Kentucky.

"Future Shock," the institute's groundbreaking four-part series released in 2011 and 2012, warned that without meaningful reforms, the pension liability would engulf Kentucky's entire economy.

Educate your inbox. Get the Bluegrass Institute's once-weekly policy update.

In a column published by the Bluegrass Institute on March 26, 2013, the late Lowell Reese, an esteemed journalist, publisher and former Chamber of Commerce executive, urged policymakers to take seriously the need to address the commonwealth's deepening pension crisis. "The soaring cost of public employee pensions in Kentucky has become a major societal issue," said Reese, who authored the "Future Shock" series. "The standard of living of all Kentuckians is at stake."

The ensuing years, which included Reese – who had been exposed to Agent Orange while fighting communism as a platoon leader in the jungles of southeast Asia – leaving us to finish this pension reform work, proved him an accurate prophet.

Pension costs consume nearly 15 percent of Kentucky's latest biennial budget passed in April by the General Assembly. Legislators passed an accompanying bill that purports to raise nearly a half-billion worth of new revenue by levying sales taxes on previously exempt products and services in order to fund increasing pension payments.

The $3.3 billion worth of pension expenditures in this year's budget are resources not available for other important services, including educating Kentucky's children, improving the state's infrastructure or hiring more law enforcement personnel to keep our communities safe. If that was the end of the story, it would be cause enough for concern. Unfortunately, the news only gets worse.

When Reese made his statement, the six state pension plans, which are under the umbrella of the Kentucky Retirement Systems (KRS) and the Teachers' Retirement System (TRS), carried a combined unfunded liability of around $31 billion. That number has nearly doubled today, in part because of new government reporting requirements and more realistic assessments regarding the plans' expected investment performance.

The alarming rapidity with which the systems' funding levels have declined should add a sense of urgency regarding the need to confront these liabilities. In 2000, the commonwealth's pension debt was a meager $960 million, five of Kentucky's six public pension systems were running generous surpluses and the Bluegrass State's pension system was among the nation's strongest.

Recent reports indicate the Kentucky Employees Retirement System (KERS) – the largest plan for nonteaching state workers – is now less than 14 percent funded, meaning the system's assets cover less than 14 percent of the benefits owed to its members. This is a far cry from the system's healthy 139.5 percent funding level in 2000 when pension experts nationwide deemed KERS one of the healthiest government-run pension plans in the nation. Only 14 short years later, the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College called KERS the most underfunded U.S. state pension plan.

Urgent reforms also are needed for the TRS, which, while appearing to be in much-better shape with its 56 percent funding level, is still in dire straits, having fallen from an 82.5 percent funding level in 2000 and now facing the reality that it's lacking more than 40 percent of the assets needed to cover its obligation to its members.

Educate your inbox. Get the Bluegrass Institute's once-weekly policy update.

What happens if drastic steps toward meaningful reform don't occur?

Defenders of the status quo, including beneficiaries' and retirees' groups, along with union leaders, often don't accept how dire Kentucky's pension situation is and the urgent need for reform. Their version of reform primarily centers on raising taxes and placing pension benefits as the commonwealth's highest priority, without seemingly much genuine regard for other policy needs.

They may be getting their way, as legislators, afraid of offending state workers and teachers, who together form Kentucky's largest single voting bloc, demonstrated their willingness not only to put records amounts of taxpayer dollars into the commonwealth's sinking retirement systems as part of the biennial fiscal 2019-2021 General Fund budget, but hurriedly enacted those previously mentioned sales-tax increases in a somewhat arbitrary manner.

These tax hikes on selected businesses reveal lawmakers seemed more willing to increase the burden for funding the commonwealth's increasing pension liability on small businesses rather than risk offending current public workers, teachers and their union leaders by freezing benefits at current accrual rates, asking beneficiaries to pay more and offering more reasonable benefits in the future.

Further rating agency downgrades resulting in increased borrowing costs for the state when issuing municipal bonds offer another serious consequence of not heeding the urgent need for meaningful reforms. Following an earlier downgrade by Moody's on July 20, 2017, Standard and Poor's downgraded Kentucky's debt on May 18, 2018 – even after the two-year budget containing more pension funding and legislation raising nearly a half-billion dollars in new taxes was passed.

In order to understand where Kentucky – and many other states also facing steep declines in their public retirement systems – need to go from here, it's vital that we comprehend how we arrived at a $60 billion unfunded liability and that the truth be told and understood.

While the 19th century Spanish philosopher George Santayana likely wasn't thinking about the arbitrary and wrongheaded decisions leading to 21st century state retirement systems sliding into dire straits, his comment that "those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it" seems nonetheless extremely appropriate, considering our goal with this first in our "Pension Shock" series is to point to key developments throughout the history of our pension system that we believe have been largely unknown or ignored.

While some policymakers, union leaders and beneficiaries' representatives show little appetite for understanding how Kentucky arrived in its current predicament, we believe it's unrealistic to try and build a structure offering solutions without a solid foundation, which, in this case, involves confronting past decisions that Bluegrass State taxpayers are paying more for today than ever before. Perhaps the redeeming factor to arise from the pain of such confrontation will be that we neither forget nor repeat such history.

It's the benefits, stupid!

Through rigorous analysis of credible data and the uncovering of startling facts gleaned from research and obtained via open records requests, the Bluegrass Institute Pension Reform Team has unearthed the true cause of Kentucky's pension crisis, which differs greatly from the typical culprits – funding deficiencies and poor investment returns – blamed by the media, politicians and state employee unions.

While the Great Recession, which began at the end of 2007, certainly did result in lower investment returns for a few years in most portfolios – including those belonging to the commonwealth's retirement system – the overall health of portfolios, whether they belong to individuals or pension plans, isn't determined by a handful of years.

However, defenders of the status quo often point to smaller and less-revealing periods of time in an attempt to defend their claims that poor investment returns are a primary contributor to Kentucky's current pension liability. From a cynical point of view, such limited views could be considered calculated attempts to avoid any discussion about the need for changing the process by which benefits are awarded.

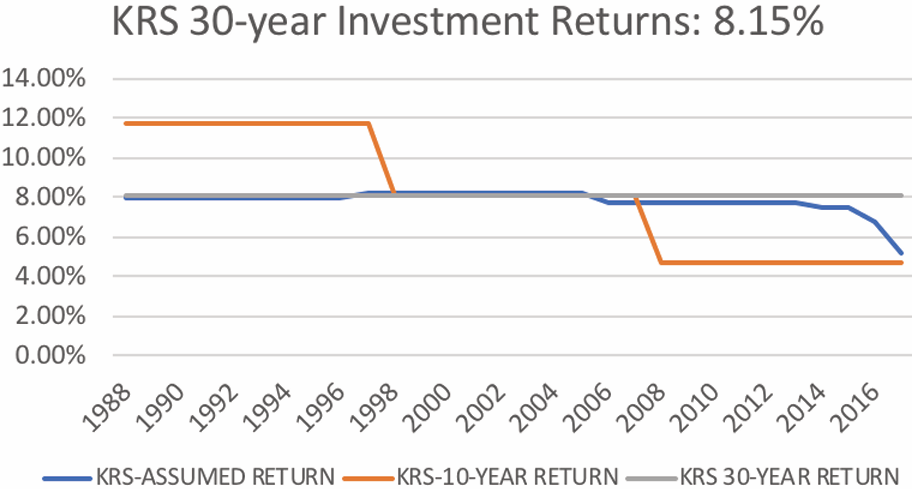

Conclusions regarding investment performance are reached by analyzing a long period of time and cycles of market gain and loss. Considering, for example, that KRS and TRS investments have significantly outperformed expectations by reaping returns of more than 8 percent over a 30-year period means the primary problems contributing to the retirement systems' decline must be found elsewhere.

Also, along with the record amounts of funding designated for the state's pension plans during the current budget, there are myriad indications that funding is not the primary cause of Kentucky's pension woes. For instance, the County Employees Retirement System (CERS), which operates under the KRS umbrella and serves local workers in the system, is required by state law to annually pay 100 percent of the Actuarially Required Contribution (ARC) to cover its beneficiaries, yet the system isn't even 60 percent funded. In fact, the CERS funding level is experiencing rapid declines, having dropped from 110.7 percent to 52.8 percent between 2000 and 2016, again despite receiving employers' full ARC payments.

While funding and investment returns certainly are critical elements to healthy pension systems, they are only two of the Kentucky pension systems' three-legged stool. Implementing effective and lasting reform will require the truth be told and understood about the third leg of that stool: benefits. A closer look reveals that the process by which benefits have been awarded to Kentucky's public employees during the past 30 years is the primary cause of the commonwealth's pension crisis.

Unfortunately, public employee union leaders and anti-reform legislators have been untruthful when discussing the true cause of the pension crisis with their constituents. Instead of being honest about the pension predicament, including how the process of awarding benefits is the chief culprit, they instead attempt to use Kentucky's pension woes to gain and retain power and influence, primarily through their resistance to change. The result is that common sense and reasonable reforms to save and put these systems on a sustainable course for the future have been marginalized or ignored altogether.

However, maintaining the status quo, resulting in the combined liability of Kentucky's public pension systems growing from $960 million in 2000 to around $60 billion today, and funding levels dropping precipitously – with KERS nearing insolvency – isn't a wise or viable option. Rather, it would be highly irresponsible, considering the pension crisis is the most looming threat to Kentucky's economy in decades and is crowding out funding for education, public safety, healthcare and infrastructure.

Finally, those on all sides of the pension reform issue, though they might disagree, should treat each other with dignity and respect while working toward solutions. The increasing amount of debate and discussion surrounding this issue should focus on data and facts – the truth, in other words – rather than harmful, emotional rhetoric that will only serve to exacerbate problems and stand in the way of finding and reaching solutions.

Benefits Granted Without Knowing the Cost

Since this analysis focuses on what we believe is the primary contributor to Kentucky's pension crisis, namely the process by which benefits are determined and awarded, here are some general statements regarding what we believe regarding the evidence we've uncovered:

Arbitrary and illegal benefit enhancements are regularly awarded retroactively to workers and retirees.

Many benefit enhancements have been awarded without a statutorily-required cost analysis to determine the monetary impact on the pension system prior to being approved.

Despite the fact that many illegal benefit enhancements have been awarded, these should not be clawed back from employees or retirees. However, a structural change in the awarding of future benefits must happen immediately.

Actuaries were complicit in enabling the practices that contributed to this crisis. At best, they accepted without question data from the systems that obviously was inaccurate. At worst, they provided cover for legislators and employees by working with them to falsely hide the true cost of decisions being made regarding benefits.

"Future is foggy for state pensions" was the title of a disturbing report on the front page of the November 29, 1999, edition of the Lexington Herald-Leader. The article reveals that at least some state policymakers knew about the need to reform the structure of benefits propped up by several years of unusually high investment returns, which, in turn, had produced large amounts of cash.

At the time of that article, the TRS was 97.3 percent funded while the KERS non-hazardous funding level was even healthier at 121.9 percent. The economy was strong, riding the wave of a stock-market performance producing abnormally high gains for pension portfolios. According to the Herald-Leader report, strong investment returns grew Kentucky Retirement Systems' assets from $3.2 billion in fiscal 1988-89 to $12.8 billion only a decade later.

Such growth in investment returns effectively masked the serious structural weaknesses of the benefit-awarding process, which would become all-too-evident a few years later when that same economy came to a screeching halt and the bubble that had carried the stock market to historically record gains would burst loudly and quickly.

The subtitle of the Herald-Leader report surely brings this point home: "Benefits are improving but with unknown effects." The truth is, Kentucky is now facing the consequences of the "unknown effects" of those generous benefits.

Taking advantage of the systems becoming flush with cash due to the aberrantly prosperous investment returns for a period of time, the Kentucky Education Association and other state employee groups requested numerous unfunded benefit enhancements for both current workers and retirees. They sought these higher benefits without proper prefunding – a key for defined-benefit systems to avoid unfunded liabilities – or perhaps even more important, without having a clue as to what these augmentations would cost. These types of unfunded, and oftentimes retroactive, benefit increases began the demise of the once-healthy and well-funded pension systems.

Since its inception in 2015, the Bluegrass Institute Pension Reform Team has focused on benefit enhancements conferred in the final years of the 20th century. It turns out we weren't the only ones concerned about the long-term impact of those increases. Gov. Paul Patton's administration, in power during that time, expressed concerns about the boost in benefits nearly before the ink had dried on their approval by the legislature.

The Herald-Leader reports the Patton administration was raising questions in 1999 regarding the impact that the cost of the pension system would have on his ability to "fund new, long-term programs in the 2000-2002 budget," and how the governor was seeking "a better handle on how recent retirement changes will figure into the financial outlook for the state."

As these benefit increases were being debated with even more sought by the unions and their public-worker constituents, serious concerns abounded about their ultimate cost, as well as the impact they would have on other services citizens expect government to provide.

It's telling that the Patton administration was concerned about the eventual cost of such large pension benefit enhancements even with the state's retirement funds were flush with cash and, in many cases, more than fully funded.

"If we continue to piecemeal these kinds of changes in benefits that impact the financial condition of these funds without looking seriously at what the long-term impacts are of those changes, we could really be impacting the long-term financial health of the system," Crit Luallen, Patton's cabinet secretary, said, as reported by the Herald-Leader.

Despite the systems' high funding levels at the time, Luallen and the Patton administration were right to be troubled not only about the enhancement of pension benefits in the years just before the page turned to the new century, but also because state employees were seeking to drive benefits even higher.

What the Research Found

The Herald-Leader's report, which outlines both the benefit enhancements obtained in 1996 and 1998 as well as the planned new increases on top of those, offers a fairly comprehensive view of the different elements used to increase public retirement checks, not just in those final years of the 20th century but throughout the history of Kentucky's retirement systems:

- Increasing retroactively to the first year of service the benefit factor used to calculate employee's pension income.

- Enhanced final compensation by changing salary determination to the highest three rather than highest five years of salary.

- Spiking of benefits by colluding with employers to get double-digit raises during the final year of work in order to drive up retirement compensation.

- Ad hoc cost-of-living adjustments (COLAs).

- Adding employee allowances such as those related to uniform, equipment or other gear to final compensation amounts.

- Prospective benefit guarantees, meaning future unearned benefits cannot be changed.

It's vital to understand, for instance, how passage of Senate Bill 142 (SB 142) in 1998 contributed to the rapid decline in KERS funding levels. This legislation:

- Raised the benefit factor for all KERS non-hazardous employees from 1.97 percent to 2 percent, applied it retroactively to all years of service and left in place an expectation that prospective benefit accrual rates would never fall below 2 percent;

- Created a 10-year window during which pension amounts received by members eligible for retirement and who went ahead and retired during that decade would be determined based on their highest three years of salary instead of the previous highest five years of pay;

- Awarded employees who retired during that 10-year window an even-higher benefit factor of 2.2 percent that would apply to every year of service retroactively – even those years previous to the 10-year window.

Thus, a KERS member who earned a 1.25 percent benefit factor in 1960, when the compensation formula was based on the highest five years of salary, and who later retired between 1998 and 2008 received a 2.2 percent benefit factor based on the enhanced high-three formula for service rendered between 38 and 48 years earlier. These benefit enhancements were not funded with either employee or employer payroll contributions but were enacted with no additional funding for two years. Worse, they totally disrupted the KERS's defined benefit system by enhancing benefits awarded – and more properly funded – at lower levels in previous years with, again, no additional funding for those enhancements.

It doesn't appear that the actuaries working for Kentucky's retirement systems and who served as the primary advisers for the General Assembly when SB 142 was debated and passed offered much beyond lip service, if that, to slow this gravy train filled with shiny new expensive benefits. In fact, it was just the opposite.

Herald-Leader reporters Jack Brammer and Bill Estep write that an in-house group created by Patton following passage of SB 142 in 1998 to “determine the impact of four pension changes the legislature approved in 1996 and 1998 … concluded that they are financially sound and that pension benefits for state employees are ‘relatively generous’ compared to those of other states.”

Yet it was Luallen’s fears that won out over actuaries’ unfounded optimism. KERS’s funding level began dropping not long after that Herald-Leader report and continues to decline even in the present, where the system is barely 14 percent funded. No wonder, as Brammer and Estep report, “the administration plans to hire an outside consultant for comprehensive study of Kentucky’s state-employee retirement system.”

Law Requiring Cost Analysis Ignored for Decades

Nearly all benefit enhancements throughout the history of Kentucky's public pension systems were granted while ignoring statutory requirements that independent cost analyses be conducted prior to legislative votes approving changes in benefits. Thus state legislators approved numerous enhancements with little idea as to their actual cost or impact on the state budget and taxpayers.

KRS 6.350, implemented in 1980, states: "A bill which would increase or decrease the benefits … of any state-administered retirement system shall not be reported from a legislative committee … for consideration by the full membership of the House unless the bill is accompanied by an actuarial analysis."

The Bluegrass Institute cited the statute in an open records request filed on March 21, 2016, with the Legislative Research Commission (LRC), seeking copies of actuarial analyses for each of the numerous benefit enhancements granted during the past 30 years. The response from the LRC's general counsel shockingly stated that "the lack of actuarial analyses has no impact on the validity of enacted legislation. In recognition that actuarial analyses are procedural rather than substantive, the Supreme Court of Kentucky found that the failure of the General Assembly to obtain an actuarial analysis under KRS 6.350 does not invalidate a law thus passed."

In our response to the LRC on March 31, 2016, we made the following comments:

"The purpose of the actuarial analysis is to determine the cost of legislation that creates new benefits or enhances existing benefits before it is enacted. The data produced by an actuarial analysis allows legislators to make informed decisions and to fully understand the financial implications of the legislation under consideration. The failure to perform an actuarial analysis makes it impossible to prefund new or enhanced benefits because the cost of new benefits has yet to be determined.

"The failure to prefund benefits creates unfunded liabilities and contradicts standard actuarial funding procedures. Consequently, the failure to comply with KRS 6.350 allows uninformed legislators to confer unfunded benefits creating unfunded liabilities at an indeterminate cost to the commonwealth and taxpayers.

"The benefits in our open records request would not have been awarded if the legislature had followed basic statutory requirements and standard actuarial funding procedures, and our pension system would be fully funded."

In dismissing the failure of the General Assembly to follow KRS 6.350, the LRC's general counsel essentially claims that legislators can pass laws placing an enormous future burden on the citizens of Kentucky without being required to follow a commonsense state statute requiring them to quantify and budget the future costs. And they have done so several times since 1980, including:

- Increasing the CERS non-hazardous benefit factor from 1.6 percent to 1.65 percent which took effect on July 1, 1984; from 1.65 percent to 1.85 percent in 1986; from 1.85 percent to 2 percent in 1988; and from 2 percent to 2.2 percent in 1990.

- Increasing the KERS non-hazardous benefit factor from 1.6 percent to 1.65 percent, which took effect on July 1, 1984; from 1.65 percent to 1.85 percent in 1986; from 1.85 percent to 1.91 percent in 1988; from 1.91 percent to 1.97 percent in 1990; and from 1.97 percent to 2.2 percent in 1999.

- Increasing the TRS benefit factor from 2 percent to 2.5 percent, which took effect on July 1, 1983, use of the "high 3" final compensation benefit calculation for members who are at least 55 years old with a minimum of 27 years of service, and the 3 percent benefit factor for service in excess of 30 years.

- All COLA increases for KRS and TRS beneficiaries and retirees.

- All enhancements to KRS or TRS health insurance benefits.

The LRC eventually supplied us with a single independent actuarial analysis related to a benefit enhancement (Attachment C). Ironically, it involved an increase in the benefit multiplier used in determining the income to be received in retirement by KERS retirees as part of SB 142 passed in 1998 and examined earlier in this report for its shocking impact on the system's funding levels. Remarkably, the actuary discouraged legislators from approving the benefit enhancements in SB 142. Among his comments:

- Raised the benefit factor for all KERS non-hazardous employees from 1.97 percent to 2 percent, applied it retroactively to all years of service and left in place an expectation that prospective benefit accrual rates would never fall below 2 percent.

- Created a 10-year window during which pension amounts received by members eligible for retirement and who went ahead and retired during that decade would be determined based on their highest three years of salary instead of the previous highest five years of pay.

- Awarded employees who retired during that 10-year window an even-higher benefit factor of 2.2 percent that would apply to every year of service retroactively – even those years previous to the 10-year window.

Conclusion

However, like is the case with many past profligate spending bills, most of the legislators received the political benefits of SB 142 reaped from overjoyed state workers who hit the taxpayer-funded jackpot but are no longer in the General Assembly as the bills come due. It's now left up to current and future leaders to do their best to clean up the costly mess left behind.

The short-term thinking of those who believe the answer to Kentucky's pension crisis is simply to continue to raise taxes and increase funding is that no only do tax hikes increase the burden on Kentucky workers, but, even worse, without structural reform, the additional dollars that higher taxes may bring will not ultimately solve the problem.

There must be a structural reform of the benefits before additional funding – wherever it's found – will significantly address one of the nation's largest state pension liability.

While we will address such structural reforms in a future release as part of this "Pension Shock" series of policy reports, understanding how past practices of ignoring cost controls and accountability measures – such as refusing to obtain independent analyses of proposed benefit enhancements – are affecting our ability to once again make Kentucky's pensions systems sustainable, as this report shows, are vital to ensuring we don't repeat the past.

Footnotes

- Reese, Lowell, "Future Shock," a series of four policy briefs addressing Kentucky's public pension crisis, Bluegrass Institute for Public Policy Solutions: http://www.freedomkentucky.org/Future_Shock.

- Reese, "Overspending: the source of Kentucky's pension crisis," Bluegrass Institute for Public Policy Solutions: http://www.bipps.org/overspending-the-source-of-kentuckys-pension-crisis/.

- Waters, Jim, "Bluegrass Beacon: Will pension funding engulf entire budget?", Bluegrass Institute for Public Policy Solutions, January 29, 2018: http://www.bipps.org/bluegrass-beacon-will-pension-funding-engulf-entire-budget/.

- "Kentucky politicians raised taxes by a half-billion dollars during session," Bluegrass Institute for Public Policy Solutions: http://www.bipps.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/Bluegrass-Institute_17-Tax-Increases-Handout.pdf.

- Loftus, Tom, "As Senate budget takes money from teacher pensions to fund others, some claim retaliation," Louisville Courier Journal, March 22, 2018: https://www.courier-journal.com/story/news/politics/2018/03/22/kentucky-teachers-retirement-system-pensions-senate-budget-bill/445502002/.

- "Kentucky State Pension Crackdown Bankrupts Health Agency," Newsmax: https://www.newsmax.com/finance/kentucky-pension-health-bankrupcty/2014/09/26/id/597145/.

- Loftus: https://www.courier-journal.com/story/news/politics/2018/03/22/kentucky-teachers-retirement-system-pensions-senate-budget-bill/445502002/.

- Reese, "Future Shock: Legislators stoking the coals on Kentucky's runaway pension train," Bluegrass Institute for Public Policy Solutions, Page 2: http://www.freedomkentucky.org/images/9/9f/Future_Shock-_Legislators_stoking_the_coals_on_Kentucky%E2%80%99s_runaway_pension_train_FINAL.pdf.

- "Rating Action: Moody's downgrades Kentucky to Aa3; outlook stable," Moody's Investors Service, July 20, 2017: https://www.moodys.com/research/Moodys-downgrades-Kentucky-to-Aa3-outlook-stable--PR_904135028.

- "S&P Downgrades Kentucky Debt," Aquila Distributors LLC, May 21, 2018: https://aquilafunds.com/2018/05/21/sp-downgrades-kentucky-debt/#.W2nGlYWcGM9.

- "Sound Solutions for Kentucky's Public Pension Crisis," Bluegrass Institute for Public Policy Solutions, Slide 15: http://www.bipps.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/BIPPS-Sound-Solutions-for-Kentuckys-Pension-Crisis-.pdf.

- Reese, Page 2: http://www.freedomkentucky.org/images/9/9f/Future_Shock-_Legislators_stoking_the_coals_on_Kentucky%E2%80%99s_runaway_pension_train_FINAL.pdf.

- Cheves, John, "Kentucky's public pension debt grew by more than $5 billion last year," Lexington Herald-Leader, Nov. 13, 2017: https://www.kentucky.com/news/politics-government/article184323228.html.

- Waters, "Bluegrass Beacon: Giving unaffordable pension benefits an economically fatal practice," Bluegrass Institute for Public Policy Solutions, May 23, 2017: http://www.bipps.org/bluegrass-beacon-giving-unaffordable-pension-benefits-economically-fatal-practice/.

- Text and vote history of Senate Bill 142, Legislative Research Commission: http://www.lrc.ky.gov/recarch/98rs/SB142.htm.

- "Sound Solutions for Kentucky's Public Pension Crisis," Bluegrass Institute for Public Policy Solutions, Slide 11: http://www.bipps.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/BIPPS-Sound-Solutions-for-Kentuckys-Pension-Crisis-.pdf.

- "Policy Brief: An analysis of Senate Bill 1," Bluegrass Institute Pension Reform Team: http://www.bipps.org/bluegrass-institute-policy-brief-analysis-senate-bill-1/.

- Ibid.

- Complete text of KRS 6.350, Legislative Research Commission: http://www.lrc.ky.gov/Statutes/statute.aspx?id=45529.

- Text and vote history of Senate Bill 142, Legislative Research Commission: http://www.lrc.ky.gov/recarch/98rs/SB142.htm.