Table of Contents

Kentucky’s education establishment is making a move to shift away from requiring public school students to take the ACT college entrance test in favor of the SAT. This will make it harder to compare Kentucky’s scores with other states. It will also make it harder for families to know how well schools have performed over time at preparing kids for college.

During the early 2000s, Kentucky lawmakers made the smart decision to require all high school juniors to take a college entrance test.

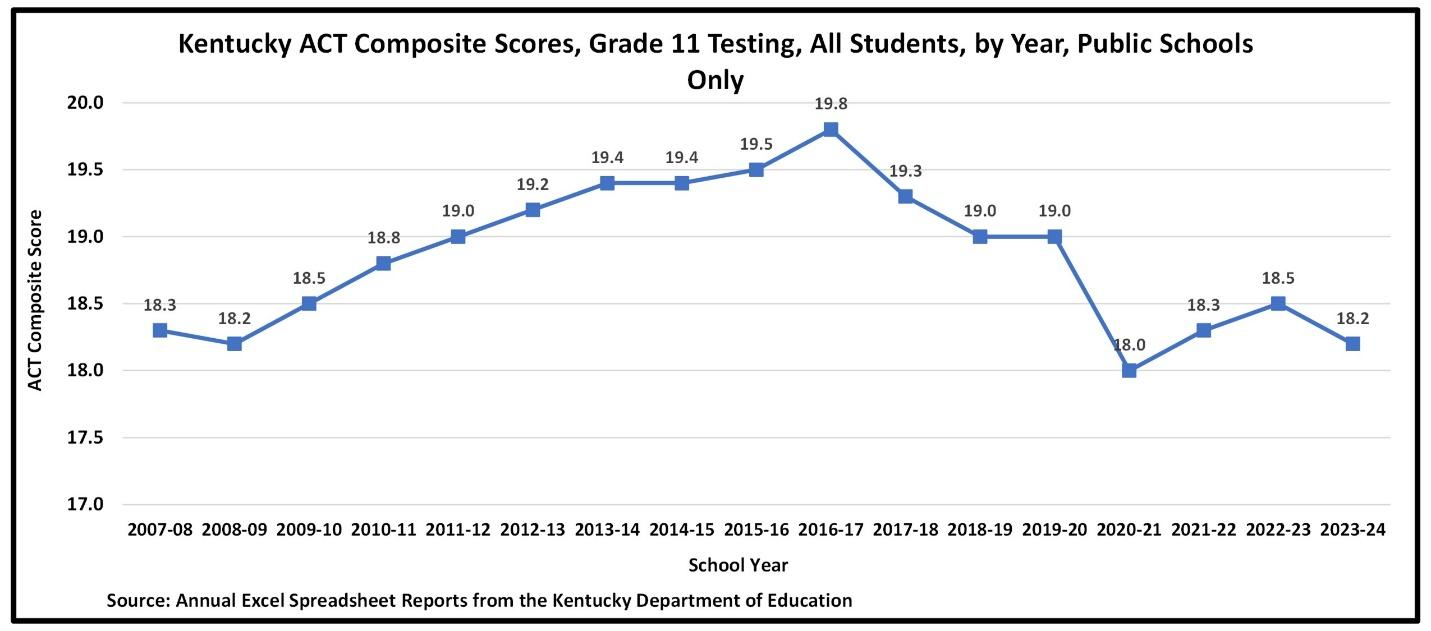

The program started in the 2007-08 school term using the well-known ACT College Entrance Test. Since then, only small changes have impacted the ACT, giving Kentucky a useful ACT trend line stretching back to 2007-08, allowing administrators and policymakers to track progress – or lack thereof – in improving educational outcomes.

Kentucky’s state-developed tests haven’t offered the same consistency. The Commonwealth Accountability Testing System, in use in 2007-08, was replaced by the Kentucky Performance Rating for Educational Progress, in 2011-12 and the Kentucky Summative Assessment in 2022. The frequent changes in state assessments, compounded by COVID-19’s impact on public schools, have prevented reliable long-term trend data from state tests.

The ACT test has proven valuable for students, helping increase college enrollment. Schools across Kentucky also use the results to improve curriculum and instruction.

So, what does the ACT trend line show?

Initially, results were promising. ACT scores, which range from 0 to 36, rose steadily from the early years until 2016-17 before beginning to decline. By 2023-24, the gains in Kentucky’s ACT Composite Score for the state’s high school juniors from 2008-09 to 2016-17 had largely been lost. A brief recovery from the COVID-related low in 2020-21 stalled by 2023-24.

Continued stability in ACT testing is essential to maintain a consistent trend line, enabling analysis of whether Kentucky can recover from the post-2016-17 slump.

However, if the Kentucky Department of Education (KDE) has its way, that isn’t going to happen. In a secretive move, the KDE issued a bid for a new testing contract and awarded it to the SAT, abandoning the ACT. Switching to the SAT, a significantly different test, will erase the ACT’s trend line, potentially masking Kentucky’s educational performance for years.

Whether the SAT can provide a comparable trend line is doubtful. After the Common Core State Standards arrived in 2010, the SAT underwent changes that raised concerns about declining rigor.

Michael Torres, a staff member at the Classical Learning Test, another college entrance test, recently noted: “Researchers at the University of Cincinnati trained an AI program to do SAT math questions going back to 2008, and it found that the test has been getting easier by about four points per year.” Torres also claims the SAT now includes fewer questions and has shortened reading passages from 500-750 words to 25-150 words.

Those changes are particularly problematic given Kentucky statutes requiring the college entrance test to assess science and English. The SAT doesn’t directly test these subjects, instead attempting to derive science scores from its reading, writing, and math assessments. With fewer questions and shorter reading passages, it’s unlikely the SAT can meaningfully evaluate science knowledge.

If the SAT generates a science score from tests designed for reading, writing and math, those assessments may prioritize science content over other areas, such as humanities or foundational American documents, which were once part of the SAT. Such a science bias could disadvantage students stronger in humanities or English literature.

ACT, Inc. has challenged the SAT bid award. For the sake of credible, consistent data on Kentucky’s education system, it would benefit students and educators if the ACT prevails.

Richard G. Innes is an education analyst at the Bluegrass Institute.